The story behind the statue which caused online outrage and censorship

What the controversy around Mother Vérité reveals about how we view women’s bodies, motherhood and public art

When The Female Lead posted about the newly unveiled Mother Vérité statue outside the Lindo Wing at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, London, designed to celebrate motherhood and the post-partum body, I envisioned comments like “finally, a real body” or “I’ve never seen a statue honouring this stage.”

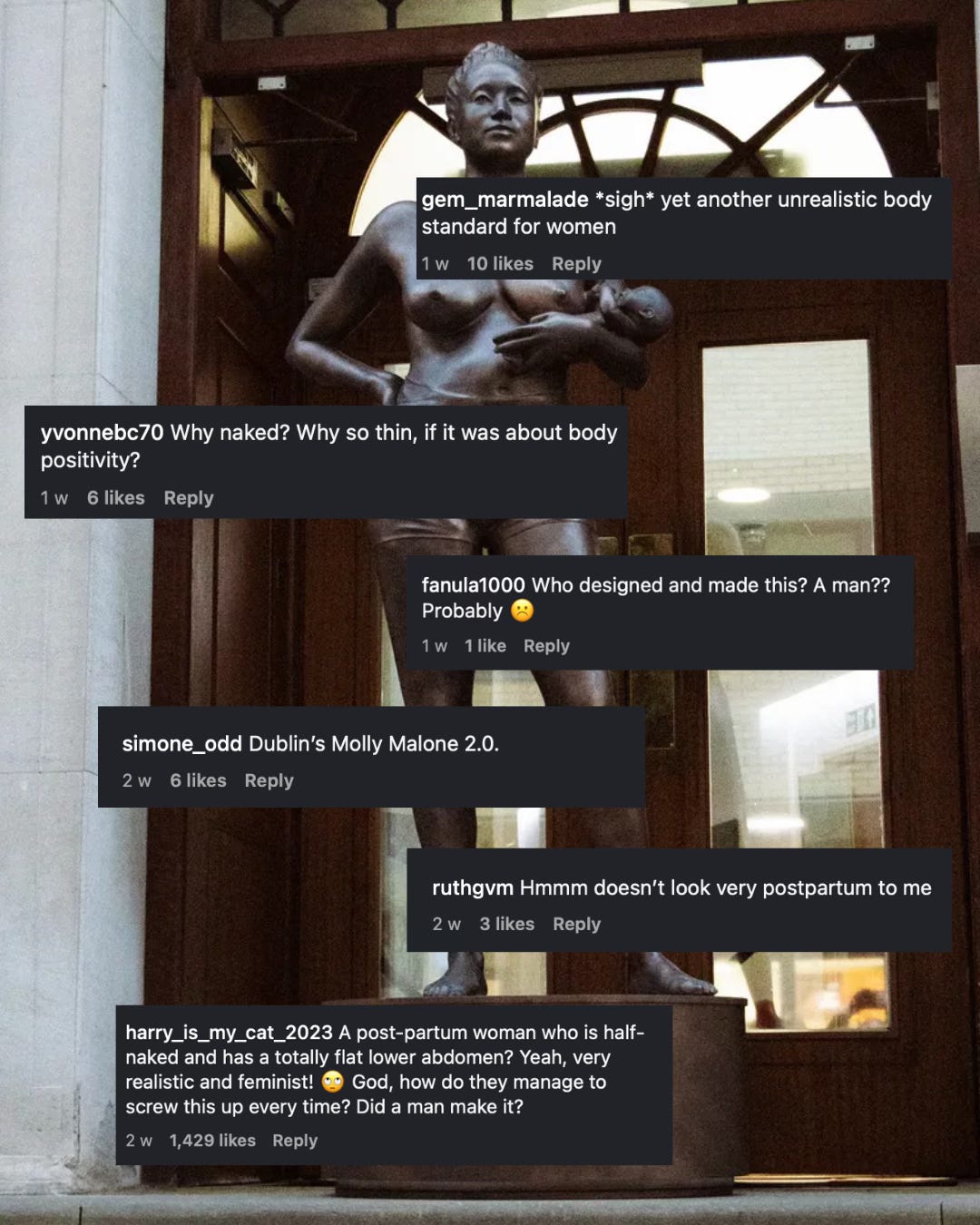

Instead, the internet had questions.

Some were convinced that this was not what a post-partum body looks like. Others questioned why Mother Vérité had to be naked, and many predicted she would be sexualised. Some compared her to Dublin’s infamous Molly Malone statue, whose bronze breasts have become discoloured after years of groping. And, of course, plenty confidently insisted that a man must have created it.

There were hundreds of comments all circling the same question: who gets to decide what a “real” post-partum body looks like, and who has the right to show it?

I will admit, I was a little disappointed at the controversy of it all. With a few clicks of research, you could find that the creators, Marine Tanguy and Rayvenn D’Clark, are both women. They had been approached by Frida, a women’s health brand, to collaborate on something genuinely unprecedented: a public statue of a post-partum woman.

Research led by Marine in July 2025 found there are, unbelievably, more statues of Paddington Bear than of women in colour in the UK. It is a funny fact until you realise what it says about whose stories we still choose to immortalise.

Both artists describe the project as a wonderful coalition. Marine was weeks from giving birth to her third child when they began, while Rayvenn had already built a reputation as an artist who “listens deeply to the communities she represents”.

“Everyone had a strong interest in making this a success,” Marine tells me.

Rather than beginning with sketches, they started with stories. “We gathered testimonies, what is right to show, what is not right to show, how do women want to be represented?” Marine says.

Over four hundred women shared their experiences of post-partum life. The team also consulted midwives, UCL researchers and post-partum specialists. Together they explored what it would look like to represent the reality of the body after birth: the swollen breasts, the soft stomach, the vulnerability and pride that coexist.

These sessions were not photoshoots. They were sensitively managed spaces, complete with an intimacy coach and a women-only crew. “No brand people, no PR, no men in the room,” Marine explains. “Just women, supporting women.” Two members of the production team were themselves pregnant or had recently given birth.

Rayvenn travelled with her 3D scanner, meeting mothers in their homes. “It was me and the mums, sometimes the dads,” she explains. “The conversations we were having really informed the artwork. We couldn’t use images of the body without being informed about what that process felt like for them.”

She later sculpted the final form digitally, combining scans from women of all shapes and sizes. “We pulled different elements from different women,” Rayvenn says. “The veins, the softness of the stomach, the cellulite on the legs. It was about honouring those details, not idealising them.”

The decision to cast the sculpture in bronze, a material historically reserved for men and soldiers, was deliberate. “In terms of legacy and hierarchy, bronze made sense,” Rayvenn adds. It places the post-partum woman in the same realm of importance.

Related articles

Listening to Marine and Rayvenn describe the process, it’s almost comical that anyone assumed a man was behind it. “The difference between male gaze and male allyship is key,” Marine explains. “No man directed this. But there were male allies, people who made it possible behind the scenes. That is very different.”

Frida, to their credit, gave full creative freedom. “They wanted to go beyond a PR campaign,” says Marine. “They let the artists lead.”

Still, both women understand why the online reaction happened. “You cannot undo the fact that we consume ten thousand images a day, ninety-nine per cent of which sexualise women,” Marine says. “We have all internalised that. Even when something is made for women, by women, it is hard to see it outside of that lens.”

For Rayvenn, the nudity conversation which followed struck a chord. “Many of the mothers were in a state of undress when I met them,” she says. “They would apologise and say, ‘Sorry, this is just how I am right now’. That is the reality of post-partum. Your body is changing, leaking, feeding, healing. Nudity in that moment is not sexual. It is survival.”

The statue’s impact is already being studied with Professor Henrietta L. Moore at UCL’s Institute for Global Prosperity through the Citizen Science Academy. Early findings from over 120 surveys show that 92 per cent of people loved the initiative and want to see more post-partum representation in cities. The responses ranged from “I cried” to “I felt proud”.

Marine and Rayvenn understand all of it. “Every emotion is valid,” Marine tells me. “Motherhood and post-partum are not a single experience. The same woman can feel powerful one day and broken the next.”

Rayvenn agrees. “If this sculpture does not reflect your experience, please add your voice to the conversation. That is the point. It is not prescriptive, it is an invitation.”

Marine adds that even her own three births were wildly different. “Each experience makes you enter motherhood differently,” she says. “That is the same woman. Imagine the variety between us all.”

They do not deny the critics’ feelings, nor do they claim this statue as universal. In fact, they welcome the debate. “The artwork is a catalyst,” suggests Rayvenn. “If this one does not speak to you, let’s make another. Why not a mother in a messy bun and an oversized T-shirt? I would love to see that too.”

Since the launch of Mother Vérité, women who took part in the project have also shared moving reflections.

One participant said, “I feel proud to be part of something so significant for the city. I’ve just had a baby and I can attest to the lack of representation of mothers. Taking part in such a supportive, female-led creative team to change that was great.”

Another called the statue “a piece of living history, embodying womanhood, strength and truth.”

One shared, “It made the parts I would normally hide, the parts society never told me to love, look beautiful.”

At the moment, Mother Vérité is just one statue. But as Marine’s July 2025 research found, fewer than four per cent of London statues represent women, and until now, none have honoured post-partum.

Marine sees the next step as pushing for real change. “Midwives are paid peanuts, post-partum depression is rising, and women are still struggling in silence,” she says. “If this statue triggers a conversation that leads to better policies or pay, that is success.”

Rayvenn adds, “We can all get bogged down in what’s there and what’s not, but if it allows even one woman to feel more seen, or one person to start a conversation based on their experience, then my job is done. I’m not here to please everyone, but to build something that creates a bigger conversation, and I do feel we’ve opened a real gateway for people, men and women alike.”

Mother Vérité makes you confront how rarely we see women like her represented. She will not be everyone’s version of post-partum, and that is exactly the point. If we want a world where every version of womanhood is seen and celebrated, we need more of them. More artists, more voices, more women in bronze.

Mother Vérité does not claim to speak for every mother, but the hope is that we start listening.

In a twist that perfectly proves the point, posts with images of Mother Vérité have since been censored with a warning of ‘sensitive content’ by Meta for containing “content that some people may find upsetting.” After being contacted by The Female Lead, Meta are investigating this censorship at the time of publication. A bronze body of a mother feeding her baby is, apparently, too offensive for the internet.

“In 2025, the recent UN Women Report raises the alarm regarding the regression and setbacks to women’s rights worldwide. So the flagging of Mother Vérité’s post as ‘sensitive content’ has been highly alarming,” Rayvenn tells me. “A very naturalistic sculpture is classified as ‘sensitive content’ that could offend. I think that it is compelling proof as to why we still have a long way to go to normalise images of women’s bodies. It is an absence that fails us all, and censoring the images of Mother Vérité is tantamount to censoring the many women who took part in this project, and is yet another example of our voices not being heard.”

It’s hard not to laugh at the irony: we can scroll past endless sexualised images of women every day, but a piece of art showing a real one is where the line gets drawn.

What a beautifully considerate and deliberate representation of the rawness and beauty of postpartum. Thank you for writing about this.

I'm not surprised at the original comments but am sad that this is the norm now. Even when there's progress (and this is significant progress) we're so trained at shouting things down and focusing on the problems, we fail to celebrate the positives. Yes, it might not represent everyone's 'truth' post partum but at least it represents truth of at least two women. Here's to more statues, more debate and more progress.