"I have reported on every major war of the last 30 years. This is what haunts me the most"

Christina Lamb, chief foreign correspondent for The Sunday Times, speaks to The Female Lead about the hidden truths of war – and why it is still most dangerous for women

Christina Lamb has spent more than three decades reporting from wars most people know only through headlines: Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Ukraine. She has survived moments that, by any reasonable measure, should have killed her.

And yet, when she looks back on her career, it is not the danger that defines it.

“What has affected me far more, is what happens to women,” Christina, chief foreign correspondent for The Sunday Times, tells The Female Lead in an exclusive interview.

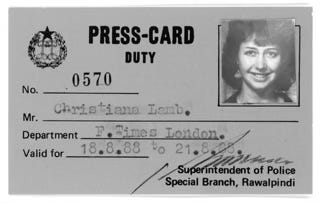

Christina’s route into war reporting was almost accidental. At 22, while interning at the Financial Times, she agreed to attend a lunch in place of the Foreign Editor. Seated beside a senior figure from the Pakistan People’s Party, she was asked if she would like to interview Benazir Bhutto [Former Prime Minister of Pakistan], then living in exile in London.

“Of course I said yes,” Christina recalls.

When Christina arrived for the interview, Bhutto had just announced her engagement to Asif Ali Zardari. “Her room was full of bouquets of flowers,” she says. “We got on well, and soon after, Bhutto returned to Pakistan to raise a movement for democracy.” Christina went back to working as a trainee reporter in Birmingham.

Months later, Christina came home to what she describes as “the most beautiful, gold-embossed invitation I had ever seen” – an invitation to Bhutto’s wedding in Pakistan.

She had never been to the country before. What she found there changed the course of her life. “It was like something out of the Arabian Nights,” she says. “So colourful, but also intensely political. I couldn’t imagine going back to work for central TV in Birmingham”

So she handed in her notice and moved to Pakistan. The last story she covered in Birmingham, she notes wryly, was about a man who had turned his car back to front.

Convincing British newsrooms to care about Pakistan was not easy. Afghanistan, however, caught their interest. As conflict intensified between the Mujahideen and Soviet forces, Christina began travelling with fighters across the border, reporting from the front lines.

Since then, she has reported from Angola, Mozambique, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Colombia, and across South America, covering, as she puts it, “most of the wars of the past 20 or 30 years”.

She is matter-of-fact about the risks. Being ambushed, shot at, forced to run for hours under fire – strangely, these are the stories people expect from a war correspondent. Christina recalls one of her closest calls in our most recent episode of In Her Words.

But these are not the experiences that haunt her.

What has stayed with Christina, is how sexual violence is used against women, not as a side-effect of war, but as one of its tools.

“People will always say there has been rape in war, which is true,” she says. “But what I’ve seen is that sexual violence is increasingly being used deliberately as a weapon.”

This is not a controversial claim. It is a documented one. The UN has repeatedly confirmed that sexual violence in conflict is often systematic rather than opportunistic. A tactic, not a by-product. As former UN commander, Patrick Cammaert put it, “it can be more dangerous to be a woman than a soldier in an armed conflict”.

“I cannot think of a single war where this has not been the case,” Christina admits.

“The stories they told are some of the most horrific I’ve heard”.

Christina Lamb

The scale is difficult to comprehend, partly because the numbers are incomplete by design. In most cases, the data “seriously underestimates the actual numbers of victims, most of whom never report to authorities”.

Even so, estimates suggest that hundreds of thousands of women were raped during the Rwandan genocide, tens of thousands in Bosnia and Sierra Leone, and at least 200,000 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the mid-1990s.

For Christina, the reality of this violence became impossible to separate from her reporting in 2014, when Boko Haram abducted 276 schoolgirls from Chibok in northern Nigeria. Some escaped. Others were released. More than 80 remain missing over a decade later.

What troubled Christina just as deeply was what happened to the women who returned. Some were raped again by soldiers who were meant to protect them. Many were rejected by their communities, treated as “sullied or brainwashed”.

This pattern repeated itself elsewhere.

In northern Iraq, Isis fighters carried out mass abductions of Yazidi women and girls, selling them in slave markets.

In Myanmar, Rohingya women fleeing military attacks described being “tied to banana trees and gang-raped”.

Some of these women escaped or were “rescued by brave people”, the stories they shared, Christina describes as “some of the most horrific I’ve heard”.

Yet almost no one was held to account.

“You had these situations where women spoke and nothing happened,” Christina explains. “One Yazidi girl messaged me and said, ‘We told our story. What difference did it make?’ I couldn’t answer the question.”

Out of that silence came Christina’s book, Our Bodies, Their Battlefield, which documents sexual violence across modern wars. Since its publication, it has already required multiple updates, expanding to include Ukraine and Palestine-Israel.

“People will no doubt say that Sudan should be in there as well” Christina adds.

What frustrates her most is not a lack of awareness. The laws exist. The resolutions exist. The language is well rehearsed.

“What’s missing,” she says, “is political will. Accountability remains the exception.” Prosecutions are rare. Consequences are rarer still.

There have been times when Christina questions the cost of her work.

“I’m taking risks, I’m putting people at risk. What difference does it make?”

But recently, while speaking with a group of Ukrainian women who had survived sexual violence, Christina was reminded why. They told her that having their experiences recorded mattered.

She recalls one young Yazidi girl who insisted on telling her story despite the pain it caused. Christina offered to stop the interview.

“No,” the girl told her. “I don’t want anyone to be able to say they didn’t know.”

This, ultimately, is what Christina’s work insists upon. That ignorance is no longer accepted. That sexual violence in war is not inevitable. It is strategic. And it continues because the world allows it to.

Who raped deserves rape.

It is challenging to acknowledge that women across all “systems”… the family, organizations, institutions, governments around the world are still defined as “less than”

If we fail to acknowledge this… if we don’t label it as the reality nothing will change ….

Never having changed my name getting married I’ve been under the illusion that more and more women stopped doing so. The reality that a “tradition” … not a law… is still in place tells us how powerful male dominated systems are … perhaps it’s beyond time to get information to women! Maintain your identity…